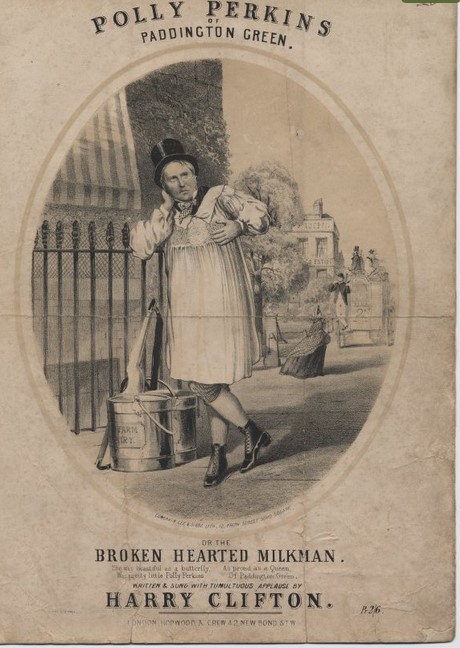

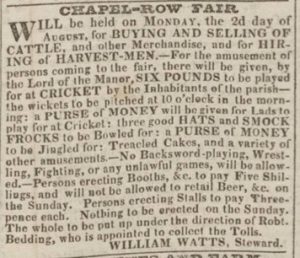

Both my daughters being ardent Harry Potter fans, the films had been on continuous cycle all weekend. As I was passing Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, which was on for the umpteenth time, I was stopped in my tracks. Hermione Granger was in her Herbology lesson, learning to pull mandrake roots, as you do with Professor Sprout, but she was wearing a smock frock. Wow! I am not sure why I hadn’t noticed before, but there you go. You start looking and they start turning up in very odd places.

In fact the whole class were smock frocked, although most of the boys were wearing more of an overall than a smock with no smocked gathering, and Professor Sprout herself, the wonderful Miriam Margolyes, was in something more akin to an academic robe with a hint of smock, the decoration of stems, leaves and vines echoing the embroidery found on some nineteenth century smocks. The earthy tones of her clothing reflect her profession and compliment those of her class well and they are worn long, like the cloaks and robes that the pupils normally wear.

So the girls got to wear the male smock. I can’t find any reference to what the costume designer, Lindy Hemming had in mind – there is quite a lot about the animatronic mandrakes and how they were made but no reference to the humble smock. In drawings of the set, the characters appear to be in their normal robes so maybe the smocks were a later addition to give it a feel of the land whilst grappling in the earth, or dragon dung, with a mandrake. There is no reference in Rowling’s writing to overalls worn – only that ear protectors were needed against the mandrake screams. Rowling describes Professor Sprout as having earth on her clothes and that the students became covered in earth by the end of the lesson. The smocks are a nice shorthand to convey that certain earthiness and physical labour in the soil needed, of course, to repot mandrakes.

The smocks look very similar to the workaday ones worn by labourers during the nineteenth century, here sported by a youth in custody at Aylesbury Gaol in 1872.

I would love to know the costume designer’s inspiration and thinking, and if they had the smocks made themselves. If anyone knows, please get in contact…

http://harrypotter.wikia.com/wiki/Herbology