In June 1891, William Gladstone, the former prime minister and in opposition until the following year, paid a visit to Holmbury St Mary, near Dorking in Surrey. He attended church on Sunday, whilst staying as a guest of fellow politician, E. F. Leveson-Gower, whose family had first built a country house in the village in 1860 and had done much to promote the area as a country retreat for the wealthy but within easy travelling distance of London by railway.

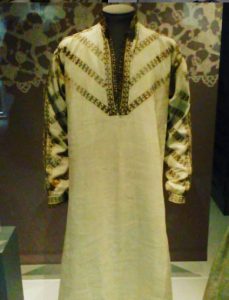

In a report which appeared in several newspapers, on leaving church Gladstone was ‘accosted by a local carrier, attired in a smock frock’. The carrier shaking hands with him, ‘ventured a few remarks upon the poor-law out-relief system’, it would appear in much the same way that members of the public are now occasionally able to ambush electioneering politicians about various causes. Gladstone had become more liberal over the course of his career, the investigative journalist, W T Stead summing this up in 1892:

At home his chief exploits have been the reform of the tariff, the establishment of Free Trade, and the repeal of the paper duty. He was the real author of the extension of the franchise to the workmen of the towns, and the actual author of the enfranchisement of the rural house holder. He established secret voting, and agreed to give effect to the Tory demand for single-member constituencies. It was in his administration that the first Education Act was passed, and that purchase in the Army was abolished. He has done his share in the liberation of labour from the Combination Laws, in the emancipation of the Jews, and in the repeal of University Tests.

W. T. Stead (The Review of Reviews, vol. V, May, 1892) p. 453.

The G.O.M., as the newspaper referred to him, that is the ‘Grand Old Man’, was seen as a friend of the working man in the days before the Labour Party, both in the town and country. The carrier, emboldened by his first contact, and acting against type as a stupid, boorish smock-frock wearer, then wrote a letter to Gladstone outlining his ideas on the out-door relief system and the incumbent government proposals on it. Delivering it to the house where Gladstone was staying, he also gave some home-made butter to Mrs Gladstone.

Both the letter and the butter were acknowledged by Mrs Gladstone, but nothing was heard from the G.O.M. himself, the newspaper reports suggesting that maybe he had run out of his postcards. Gladstone was a well-known user of postcards and many survive from his hand. Growing in popularity since the Newspaper Postage Bill of 1870, postcards were at first seen as ridiculous, having no privacy, insulting in their briefness to the receiver, and debasing the art of letter writing with their necessary brevity. For Gladstone, the economy of both the space and the cost seemingly appealed to him and he used them widely. The Times reported on the history of the postcard on 1 November 1899, noting that Gladstone had ‘made countless numbers happy by the receipt of a card bearing his well-known writing’. Thus by the end of the nineteenth century, they were seen as ‘most useful’ and ‘indispensable’, the text messages of their day perhaps? The newspaper report in 1891 remarked somewhat sardonically about this encounter in Surrey however, that Gladstone ‘ought to have sent his customary postcard giving his views on butter-making’ to the carrier. Although a swipe at Gladstone, it also perhaps, backhandedly, re-enforced the view for newspaper readers about those wearing smock frocks – they would understand comments about butter making, not Gladstone’s answer to a query about poor law proposals, despite evidence to the contrary.

http://www.attackingthedevil.co.uk/reviews/glad2.php