Before it closed at the end of October for the season, I paid a visit to Kelmscott Manor, the country home of William Morris from 1871, deep in the heart of the Oxfordshire countryside, close to the banks of the river Thames. I was on the hunt for smock frocks (though I did get distracted by the guttering…).

The aesthetic of smocks, as an unrestrictive dress shape, was undoubtedly popular with those seeking dress reform in this period, away from the sheath-like encasements, augmented with bustles, flounces and swags, of contemporary fashionable dress.

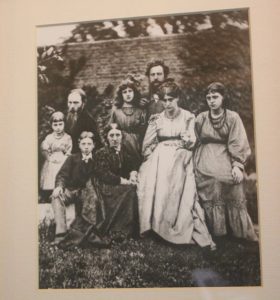

In this photograph, in the entrance hall of Kelmscott, of Morris and Rossetti with their families, Morris’s wife Jane and her two daughters wear loosely gathered and belted dresses which became known Pre-Raphaelite dress and was worn by those closely associated with the movement. Indeed, Jane was painted by her lover Rossetti in 1866-8 in his famous portrait, ‘The Blue Silk Dress’, wearing another similar softly gathered dress, a painting on display at Kelmscott, its jewel like colours shining out in the autumnal gloom.

These dresses were also akin to the medieval styles that Morris used for his tapestries and stained glass, amongst other things, during the same period. Their looseness and unconstructed nature, in contrast to the rigidity of contemporary fashion, which relied on structure and a defined silhouette with the crinoline and later the bustle, show a link to the smock.

A newspaper article from 1888 described a visit to the Merton Abbey works, Morris’s craft workshop/factory, in Surrey:

What strikes the visitor first of all in this rambling, delightful place where everything is quaint and striking is the figure of one of the workers, a white-haired man, with flowing hair streaming from below a large ‘penny’ hat; for his ordinary dress he wears a long blue smock-frock, daintily-embroidered around the neck and on the shoulders…

He is the foreman of the stained glass department and one of the original workers in the factory, having been there since 1860 when Morris first started production, and so a trusted friend of Morris. How much this was a uniform or just the choice of an individual artisan is not explained in the newspaper, the smock just feeding into the idea of quaintness. As his appearance is described as ‘striking’, maybe it was an individual choice. I therefore hoped to find more evidence of male smocks at Kelmscott.

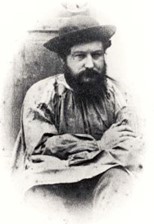

This would have been an area and a period, from the 1870s, when smocks would still have been worn by the local rural population, although their use was starting to decline. So what is surprising then is perhaps the lack of smock frocks, aside from the loose Pre-Raphaelite dresses of the women. Does this suggest that, in general, they were not particularly well-crafted during the 1870s, to merit the attentions of the ‘founder’ of the Arts and Crafts movement? Many were workaday and bought as cheaply as possible from ready-made clothing shops – it is perhaps not until later in the century, that best smocks began to be seen as something worth preserving and their associations with quaintness and craft began, as worn by Morris’s own worker when they had all but disappeared from the countryside a couple of decades later. Morris himself was photographed in an undated portrait wearing an over-shirt or perhaps a smock, as his work clothes. They were being used as an overall but the association with hand-worked rusticity had yet to begin.

Perhaps the most intriguing thing I discovered was Morris’s caped overcoat, hung in the corner of the North Hall of Kelmscott. It was very evocative, as often clothing is, of the man who wore it, especially as we know what he looked like. Plain and austere, it catches the attention of visitors to the house as something intimately connected to the man, close to his body and perhaps imbibing his odours and body shape.

It was not a smock but as I began to look more closely I saw the label and started to wonder about Morris’s relationship with his clothes. It was labelled ‘H. J. Nicoll & Co.’ and Nicoll’s were originally ready-made clothing manufacturers who made their fortune in the 1840s and 1850s manufacturing paletots, a gentleman’s overcoat. They widely advertised their ready-made coats in the press at the time and also sold wholesale to tailors and outfitters to sell on. The problem was the way that these ready-made coats were manufactured, especially in the days before the sewing machine. Nicoll used middlemen to employ thousands of London East End workers to sew their garments, largely women. These out-workers worked for very little and had a precarious existence, partly because the work was seasonal. The profits all went to the middlemen, and mainly to the contractor, Nicoll. Contemporaries were well aware of the situation, with Charles Kingsley, author of the Water Babies, exposing the exploitation in his work Cheap Clothes and Nasty of 1850, along with the journalist Henry Mayhew.

The profits, however, allowed Nicoll to have a swanky Regent Street shop with large plate glass windows and a feeling of modernity – a palace of retail. They also gained an air of respectability, boasting that their customers included Prince Albert and the Duke of Wellington, and the company survived and prospered until the 1960s. Morris is said to be depicted wearing his Kelmscott coat on his statue on the exterior of the V & A museum.

Much as our clothing is manufactured today in the sweatshops of Asia and we don’t necessarily think about the human cost that went into the manufacture of a garment when we put it on, and how that might sit with our ideological or political beliefs, Nicoll and other similar ready-made clothing manufacturers, including those making ready-made smock frocks, maintained successful businesses throughout the period based on domestic manufacturing often in sweatshops. Their customers remained happy to buy from them whatever the origin of the garment’s manufacture, if it was the piece of clothing that they wanted, the price was right and the garment was easy to purchase. The idea of the hand-crafted beautiful object did not seem to extend to Morris’s own clothes and the smock was yet to be seen as such too.

For more about Nicoll see Clare Rose’s work:

http://www.maneyonline.com/doi/full/10.1179/0040496914Z.00000000039